While we all run at different paces and in different places, many of us share a common goal — to get faster. It might be faster than your buddy, or faster in your next race, or even faster than yesterday?but the minute you hit "stop" on your watch it's running human nature to start doing the math on how you can improve. Problem is, with so many programs promising fast gains, the vast majority of runners don't conceptually know how to begin getting faster. Should you run longer? Should you cap your heart rate? Do you need to go faster? Is it the shoes? The answer, actually, is closer than you think: if you want to become a faster runner, you need to focus on the pace your running muscles can sustain.

Running Events Near You

The Heart of the Problem

If you are like 80 percent of the runners on the road today, you own and use a heart rate monitor to guide your training. If not, you have probably seen the color-graded chart of exercise intensity on the wall of your local YMCA or gym, encouraging you to hit a target heart rate for specific exercise benefits.Contrary to popular belief, cardiovascular fitness is not a good marker of running fitness or even running performance. While it's better than nothing at all, it's deceptive in that many runners are lead to believe that their Heart Rate is an indicator of their fitness. Heart rate looks only at the stress on the cardiovascular system–or to paraphrase, what your muscles are demanding of your body. As such, Heart rate is removed from the central proposition of your training — how hard your muscles are working. Add to this the fact that HR is also influenced by factors like dehydration, heat and stress.

In fact, you can gain fitness with no change in HR; you can have different HRs for multiple repeats of the same test and still have not gained any fitness. For more information in this area, you can refer to the following resources: VO2, Lactate Threshold, VO2max, and Endurance Performance, Hagberg, J. M. (1984). Physiological implications of the lactate threshold. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 5, 106-109; and Maximal Oxygen Consumption – The VO2max.

Your Running Muscles

The easiest way to understand this concept is just this: your muscles are what power you around the block to a five-mile personal best effort--Not your heart. Your heart tells you how hard your body is working, but the only thing that can make you faster on your next attempt at that run is stronger legs. Inside Marathon Nation we measure your functional running fitness via a 5K test so we can get your pace for that effort. We then use that effort, the one you physically did (not from a chart), to map out your training intensities across the program. This leads to focused workouts that are essentially personalized to your current proven fitness levels.Pace is a better gauge of intensity because it directly relates to muscle loading or motor unit recruitment (muscle work). An 8 minute/mile is the same effort in your neighborhood as it is on race day. Try pegging your run pacing to a specific heart rate and you could be doing a 5 mile loop at 8:30s one day and 7:30s the next. There's simply no consistency.

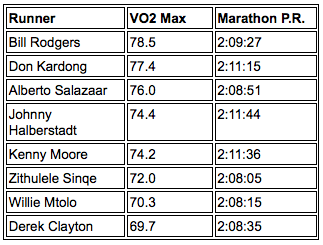

In fact, at the intensities that we race (from the 5K to the marathon), the pace at threshold is a much more useful marker. Exercise physiologists have begun to note that many training programs result in improved performance, but do not improve VO2 Max significantly. This has led many to shift from using VO2 Max as a marker of fitness to using power/pace at lactate threshold. As it turns out, VO2 max seems to be a rather poor predictor of endurance performance. Consider the following examples: