The physiological borderline between moderate and high intensity is the respiratory compensation point, which falls at about 92 percent of maximum heart rate for trained endurance athletes. Any training you do above this threshold will affect your body in more or less the same way. Swimming, cycling or running at 98 percent of maximum heart rate will stimulate adaptations that boost your ability to sustain high submaximal speeds, and so will training at 93 percent of your maximum heart rate. But your body can go a lot longer at 93 percent of maximum heart rate than it can at 98 percent, so a set of long intervals performed at the former intensity has more potential to enhance intensive endurance than does a set of short intervals at the higher intensity.

For the trained triathlete, heart rates in the range of 92 to 94 percent of maximum correspond to race pace for swims of 1 to 1.5K, cycling events of 15 to 30K, and runs of 5 to 10K. (Bear in mind that maximum heart rate is lower in the pool than it is on the bike, and lower on the bike than it is on the run.) In other words, the average trained triathlete can sustain efforts just above the respiratory compensation point for 12 to 40 minutes in competitive circumstances depending on their fitness level, the specific discipline, and their individual strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, workouts that feature intervals of 3 to 8 minutes and between 12 and 40 minutes of total work at this intensity are manageable for most athletes.

More: Calculate Your Training Heart Rate Zones

Long Interval Workouts

These parameters can be translated into distance, which makes long intervals easier to do in the pool and at the running track:

In the pool, you might swim 4 x 400 meters at your 1,500-meter race pace with a 2-minute rest after each interval.

At the track, you might run 5 x 1,000 meters (2.5 laps) at your 5K race pace or a bit slower with a 400-meter (one-lap) jogging recovery after each interval.

You can measure long intervals by distance on the bike as well (the appropriate range is 1 mile to 5K), but time-based intervals are more commonly used.

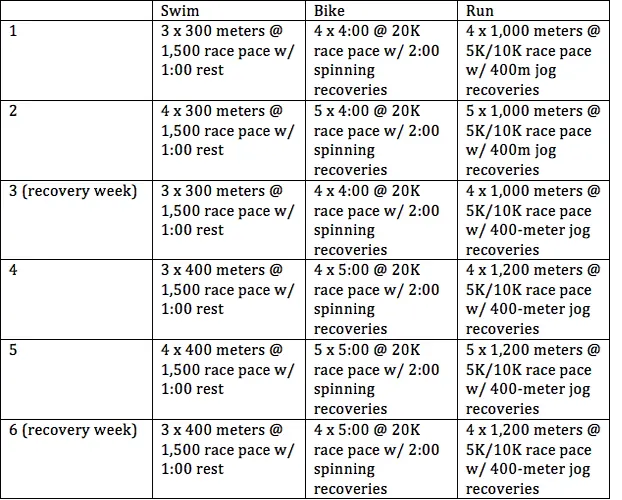

If such workouts are not a regular part of your training regimen already, they should be. A small amount of this type of training goes a long way. And because long intervals are quite challenging, doing more of this type of training can put you at risk of burnout. I recommend doing 6 to 8 long interval workouts in each discipline per training cycle. These sessions should come toward the end of the cycle, close to your most important race. Arrange them progressively, starting with shorter/fewer intervals and extending the sessions incrementally from week to week. Following is a sample six-week progression. Warm-ups and cool-downs are not included.

Long intervals such as those described in the table are not meant to replace shorter, faster intervals. But the near-sprints should be emphasized earlier in the training cycle and then move back to a supporting role in the final weeks before an important race. Give it a try and you'll see why!

Sign up for your next race.

Sign up for your next race.